We were introduced to pen and ink in grade three. In those days we used long wooden dip pens that had replaceable nibs.

In the corner of every desk there was a metal inkwell with a hinged lid. Our grade three teacher kept the inkwells filled with dark blue ink.

In grade four or five, we had to supply our own and somehow, when we purchased our school supplies at the beginning of the term, the ink I bought wasn’t blue or black, but turquoise. I’m still surprised I was allowed to use it.

When I was ten or eleven years old, I wrote my first poem.

I remember how it looked, several verses that took up an entire page, written carefully by me on lined paper, in vivid turquoise ink.

I was pleased that I had written a poem, but I wasn’t satisfied with it. I had never seen a boy dip a girl’s pigtail in an inkwell. I had heard about it somewhere. My poem was not an original idea and I knew that.

At the time, however, as you can see in this picture, I had long pigtails.

I was also unhappy with one line of the poem, the only line I remember, that said, “in and in the ink did seep,” but I didn’t know what to do about it.

Shortly after that, undaunted, I wrote my second poem, prompted by a radio announcer who invited listeners, one Sunday morning, to send him poems about cats. It was a contest, although the prize may have been only the chance to have your poem read on the air.

Immediately, there in our living room, on a small scrap of paper, in pencil, I wrote a poem about a cat.

It was shorter than my first poem, and I’m fairly sure the word “paws” was in it. Other than that, all I remember is that I knew it was better than my pigtail poem.

I showed it to my mother. She read it, said, “I’m keeping this,” and tucked it into the pocket of the rose striped housecoat she was wearing. It was never seen again.

About the same time, I wrote a short story. It was a western, but I lost interest and rushed the ending, knew it wasn’t good and didn’t write another story until I was considerably older.

After that there were compositions to write in school, from grade eight onwards, that I did very well, and essays in college, which I did fairly well.

When I was in high school, my mother, here in a much enlarged photo,  bought me a small desk. Not much more than a table, with only one shallow drawer, it was plain and sturdy and made of dark stained oak. Mom bought it at a second hand store, where all the furniture in our house was purchased.

bought me a small desk. Not much more than a table, with only one shallow drawer, it was plain and sturdy and made of dark stained oak. Mom bought it at a second hand store, where all the furniture in our house was purchased.

In my second year of college, I took Creative Writing.

There were six people in the class, as far as I remember, although now I can picture in my mind only three of the others. Two of us were female and became good friends that year. Occasionally there were drop-ins.

It was an informal class that I think met once a week for that term, from September to April. We sat around a table. The instructor, who turned thirty that year, as he told us one afternoon when we were drinking coffee  in The Caff, was relaxed, friendly, respectful and enjoyed hanging out with his students, but he took his work seriously and had high standards.

in The Caff, was relaxed, friendly, respectful and enjoyed hanging out with his students, but he took his work seriously and had high standards.

In every class, he read to us something one of us had written and we discussed it. It wasn’t always comfortable.

Happily, at home at my small oak desk, I wrote at least the thousand words we were required to produce each week. Usually, it was a story. Once we were asked to write a one act play. Another time each of us wrote one act of a longer play, passing it along week after week until it reached me, because I had won, when we drew lots, the opportunity to write the last act.

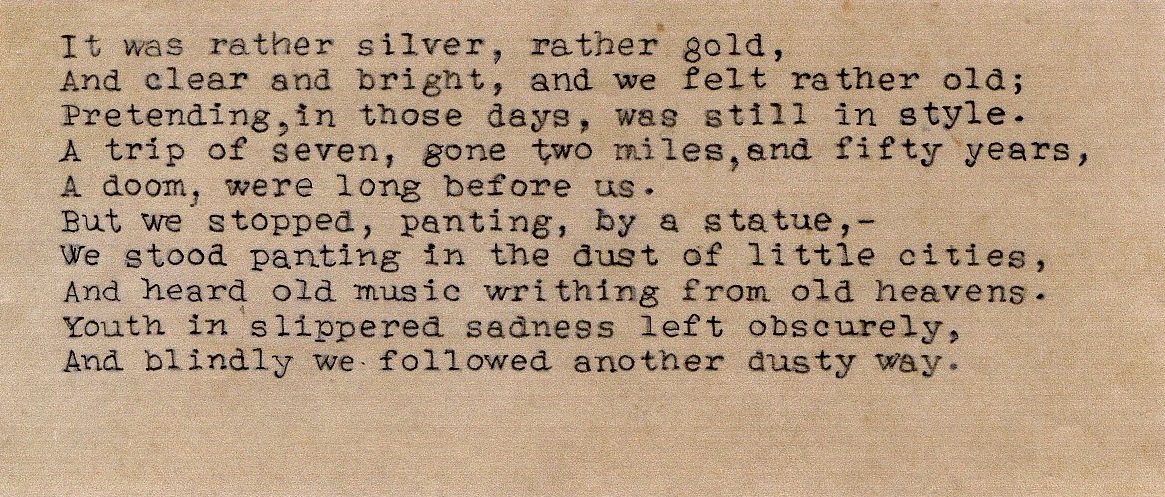

Early on, perhaps as our first assignment, as if he took for granted that we had all been writing poetry, our instructor asked us to submit a short collection of poems. Now that I look at them, I see that a couple are dated and I must have written them earlier, but I sat down and wrote a few more, probably in longhand, then typed them on my little portable, apparently on newsprint.

I submitted seven poems as POEMS WITHOUT TITLES.

This one is so faded, I’ve darkened the print with pencil.

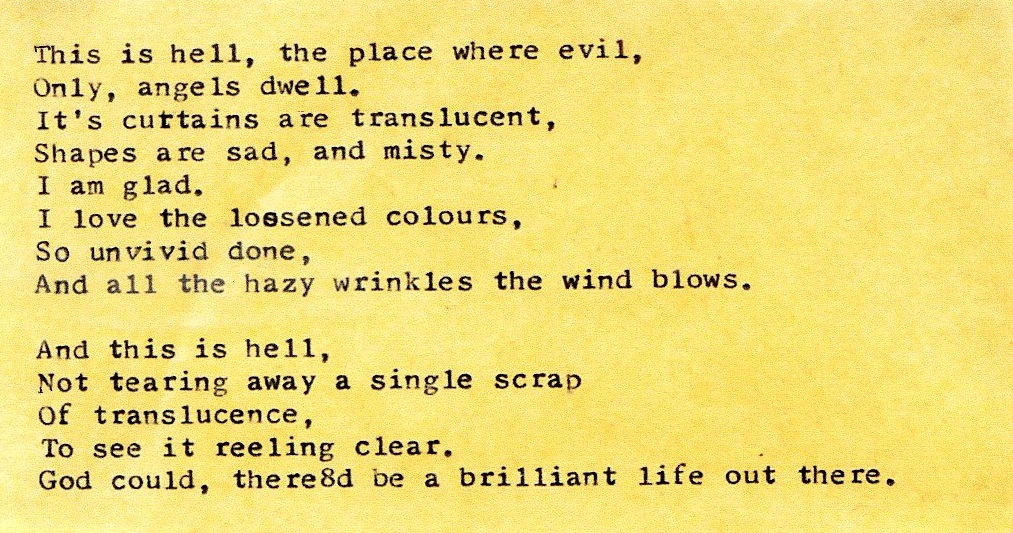

This one has stood the test of time much better, but notice the last line, where there’s an 8 instead of an apostrophe.

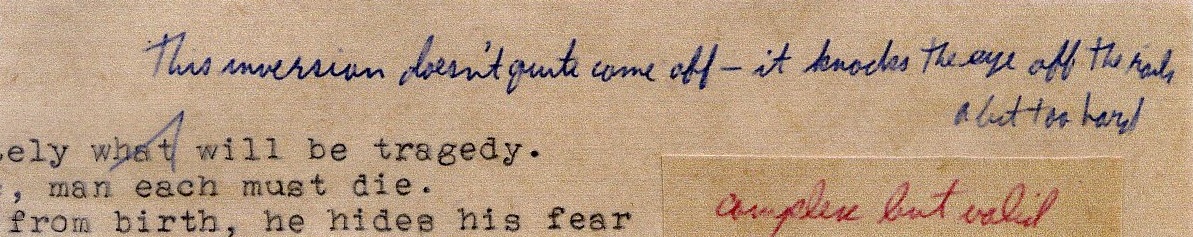

Yes, I kept them, because they earned an 86, and even better, the instructor’s comments.

“This inversion doesn’t quite come off – it knocks the eye off the rails a bit too hard” he wrote about a line in one of the poems, and he described one poem as “complex but valid.”

They are his only comments until, at the end, he offered this assessment:

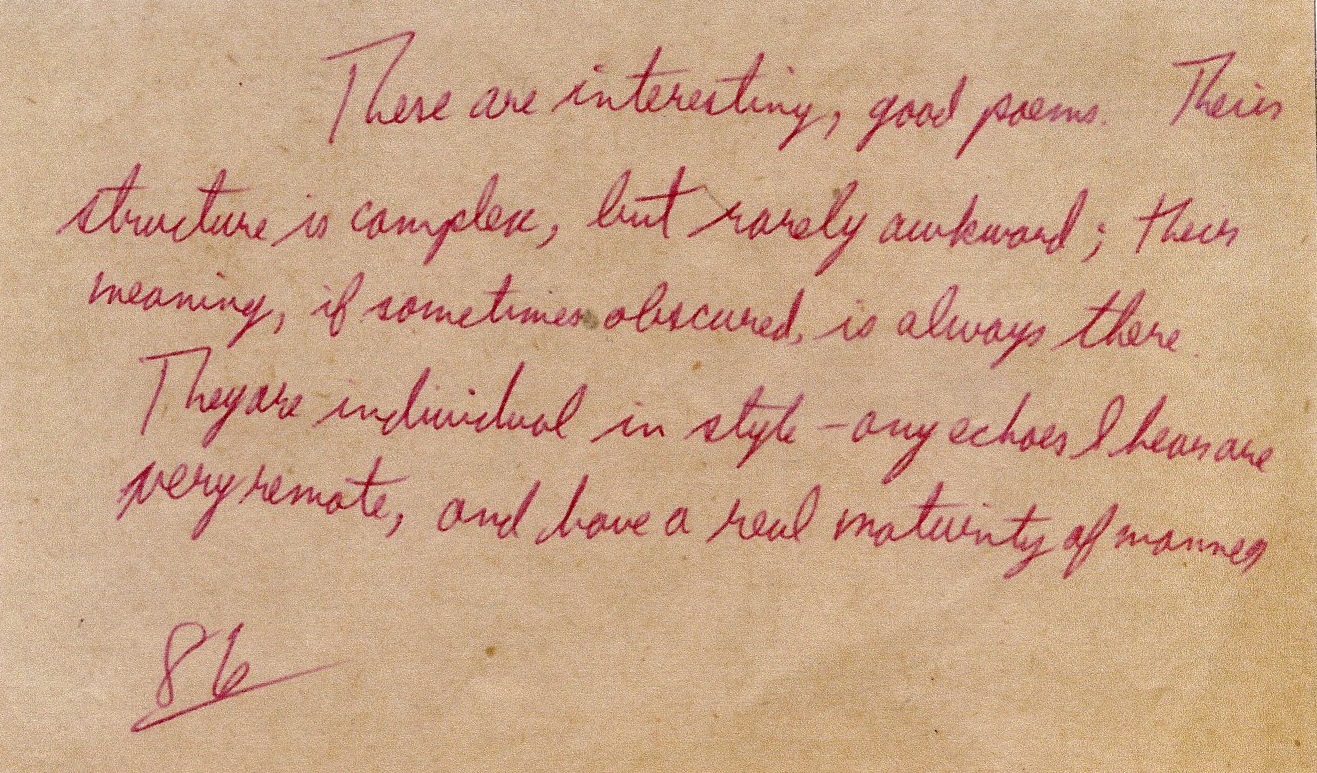

These are interesting, good poems. Their structure is complex, but rarely awkward; their meaning, if sometimes obscured, is always there.

They are individual in style – any echoes I hear are very remote, and have a real maturity of manner.

Then, in April, it was over.

In the next two years, I wrote papers for the courses I took in Modern,

Contemporary and American Literature.

In summers I was a bus girl and a waitress, then had an easier job, working behind the counter at a dry cleaner’s.

I was an efficient bus girl the summer I worked at a small motel restaurant, where I cleared tables, loaded and unloaded the dishwasher, peeled potatoes and, using an apparatus that had a sort of pump handle, pressed the peeled potatoes through a strong metal grid that turned them into raw French fries. I wore a pink uniform and a little white apron. It was a job I was totally suited for and should have stayed with all summer, for less pay, instead of allowing myself to be promoted to waitress. I was always better at dealing with things than with people.

Later, while raising my family, I worked from home as a bookkeeper, read a great many books, both fiction and nonfiction, and when the kids were grown up, although I wrote the odd poem and was working on a novel, I allowed myself to be sidetracked by my new hobby, working with clay at the local community centre where there were kilns and glazes and a slab roller.

I did make some pots, but sheep, impressed with textures knitted or crocheted by me in cotton yarn, were my specialty. I sold them at craft fairs. I also produced mountain goats and reindeer with fragile antlers and one year I made a few palm trees and was surprised how quickly they went because people wanted them for their nativity scenes.

TEEKA AND TUGG

TEEKA AND TUGG took years to write. It began when my grandson, Rowan, was in kindergarten. Whenever he stayed overnight at my house, which was frequently, I read him a bedtime story. One evening he announced that he didn’t want me to do that. He wanted me to tell him a story. I accepted the challenge. Sometimes I had an idea well ahead of time and had all day to think about it. Sometimes it wasn’t until bedtime that I came up with something. It was never a long tale. The quality varied. At the end of it, my little critic, as he lay in bed, would let me know what he thought. “That was good,” he might say, or “No, not very good,” but I always felt that every attempt was appreciated. Of course his mom and dad and grandpa read good stories to him, and I did too, but not at bedtime.

Very soon, every story I told him was about a brother and sister, Teeka and Tugg, and their far-fetched adventures. A goldfish pond was also important in the stories.

I began to write down the more successful stories and eventually, over the years, expanded them. Rowan read them and offered feedback as they were turned into a novel.

TYPEWRITERS

I was in high school when I decided I needed a typewriter.

To earn the cash to buy it, I signed up for berry picking, that was, in those days, a summer job for teens.

We had to be at the bus depot perhaps as early as six thirty in the morning, with a packed lunch. A comfortable chartered bus took us to the loganberry farm.

The farmer weighed what we picked because that was what our pay was based on. The berries in our pails were then emptied into a huge vat, along with a few leaves and the occasional bee or wasp.

The mornings were cold. The afternoons were hot. Loganberry bushes had thorns. Berry juice stung our fingers.

I lasted seven days and didn’t earn enough. My mother and I went to the store and together bought a small portable typewriter, for which Mom paid much more than I did.

I may have wanted it because I was planning a novel that was never written and thought it had to be typewritten. I must have been aware, too, that typing was a useful skill in those days. I probably could have taken typing at school instead of extra art classes in the three spares I had every week. It would have been a mistake.

I bought a book and practised typing on my own. I learned to touch type except for the numbers, and I’m glad I did now that I’m writing and have a computer, but on a typewriter I was never, ever, fast or accurate.

Even in college, I sometimes wrote my essays in meek, tiny, but legible handwriting.

Later, when I worked at home as a bookkeeper, and was paid a flat rate, not by the hour, I typed invoices on an electric typewriter. The keys didn’t have to be pressed as hard and the machine had a replaceable correction tape that could white out mistakes quickly, although not perfectly.

Eventually, we acquired a printer and a computer.

If computers had been available when I was in college, writing a paper on H.G. Wells or Faulkner, for instance, I could have moved paragraphs and sentences easily from one place to another and made corrections immediately. I wouldn’t have had to remember to leave enough space at the bottom of the page for the footnotes, and as a finale, could have expected the printer to produce a good copy.